Given the opportunity to visit St. Louis, I took a little time to dig into the history of one relative who moved to that city from upstate New York. This is my 1st cousin 3x removed, Joseph Harrington. I thought that this would be very straightforward: find burial sites, take a look at some old houses, and generally get a feel for the place. And that is how it went down during my time in St. Louis, at least until I started to dig a little deeper. The story then became, at the same time, more complicated and infinitely more interesting.

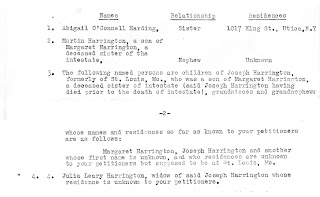

Let me try to put Joe in some context. First cousin three times removed means that his grandparents, William O’Connell and Margaret Murphy, are my 3rd great grandparents (that’s 2 generations away from him and 5 generations from me). I’m related to him on the Harrigan side of the family, and, no, that wasn’t a misspelling in the first paragraph. His surname was Harrington, and he actually has no Harrigans in his ancestry. But as with all things Harrigan, the best starting point is the probate records from 1919 filed for the estate of Nora O’Connell. I described these earlier in my post about Tom Harrigan. In this case, one set of potential heirs or claimants to Nora’s estate were (numbers 3 and 4):

That gives you many of the names of the family relevant to the story. The main ones that are missing are, first, the unnamed child of Joe and Julia: this was a daughter named Julia Josephine. The other important person was Joe’s brother-in-law, a man by the name of Joseph O’Leary. First, though, let me recount the straight-line story of Joe Harrington’s life.

Joseph Francis Harrington was the second son of William Harrington and Margaret O’Connell. I’m not sure if his parents married before or after emigration from Ireland to the United States. My first records are when William Harrington bought property from Lorenzo Carryl in the township of Salisbury in Herkimer County, New York. This land is north of the city of Little Falls, abutting Spruce Creek on its eastern border. Since the original purchase the creek was dammed to produce a reservoir that provides Little Falls with water. The Harringtons had three sons: Martin (born 1868), Joe, and Thomas. There is only a single record for Thomas that I’ve found, the 1875 New York census, and it says that he was 3 years old. Thomas is never heard from again, and so I infer that he died sometime in the period 1875-1880. In that same 1875 census Joe’s age is said to be 5. However, in all the subsequent records Joe’s year of birth is recorded as 1872, and not 1870.

Joe graduated from high school in Little Falls, passing the Regents’ examinations in arithmetic, grammar, rhetoric, and Caesar’s commentaries. He then went on to college, enrolling in the Catholic school Mount St. Mary’s College in Emmitsburg, Maryland, from which he graduated in 1896. From there he enrolled in post-graduate work of some sort at the Catholic University of America in Washington, DC. He seems to have been a very good student. I haven’t been able to track down any details about what he was doing in Washington. However, in 1897 the Little Falls Evening Times reported that he was going to move to St. Louis to take on the job of a reporter with the Globe-Democrat, specifically in the “church department.” This took a bit of inside influence: “The position was secured by Congressman Richard Kearns, whose sons were classmates with Mr. Harrington at the Washington university.” As best I can tell, though, there was no such congressman at roughly this time. I believe the reference should have been to Richard C. Kerens, a St. Louis millionaire and political aspirant. Although he was a member of the Republican National Committee and tried to gain the Republican nomination for Senator, he was never elected. However, he did serve as Ambassador to Austria-Hungary in the Taft administration. His sons were Richard Jr. and Vincent.

I rummaged through pages of the Globe-Democrat, but the stories there had no by-line. It doesn’t seem that Joe stayed with the newspaper too long, anyway. In the 1900 census his occupation is “Com’l traveler (books)”; I presume that means a travelling salesman. At some point he worked for the Dodd-Mead Publishing Company. Meanwhile, on 11 May, 1898 he married a young woman from St. Louis, Julia H. O’Leary.

Julia was the only daughter of Cornelius O’Leary (1835-1891) and Mary Mulroy (1850-1876?). She had two brothers, Joseph (1873-1941) and Leo (1874-1889). Cornelius was a lithographer or printer. I’ve not been able to find much at all about Mary Mulroy. In the 1880 census Cornelius already is recorded to be a widower. There is a Mary Mulroy buried in Calvary Cemetery in St. Louis who died in 1876. The timing is right, and I suspect, but can’t document, that this was Julia’s mother. Julia was living with her brother Joe when she married Joe Harrington, and the three of them continued to live together for a few years. Joe O’Leary was an artist: he drew cartoons for most of the newspapers in St. Louis as well as drawing advertising, theatrical, and circus posters. The Harringtons had three children: Marguerite (born 1899), Joseph Jr. (born 1902), and Julia Josephine (born 1903).

The thing that makes this story interesting to me are a couple of dramatic changes from the expected timeline. The first of these occurred in 1905, when Harrington left the book business and turned to making cars. In 1907, with $2500 in cash, he and Julia, together with another couple, Robert and Grace Horne, filed articles for the incorporation of the Victor Automobile Manufacturing Company. The Harringtons and the Hornes each held 125 shares, the husbands each had 124 shares, while the wives had a single share apiece. In 1908 Horne was cited as the president of the company, with Harrington the vice-president. When Horne died the next year, Joe became president (I’m not sure what happened to those 125 Horne shares). His salary was $30/week along with about $100/month in commissions. A far cry from modern CEO salaries even when inflation is taken into account!

When I first learned this, I was puzzled: wasn’t Detroit the national center of automobile manufacturing? Well, yes, but in those early days there was a lot of competition, and St. Louis was a hub of such activity. The Victor Motor Car Company (another name for the business) produced both commercial and pleasure vehicles. In later years the commercial vehicles were a profitable enterprise, but the personal cars lost money for the company. For reasons that I’ll explain shortly, the company made cars only until 1911. There were a surprising number of companies around the country that sold cars under the name “Victor,” so a bit of care is needed when searching for information on Harrington’s products. Apparently, though, there is still one of their 1907 high-wheelers out there that still runs (although obviously with lots of rebuilt parts). I was also able to find some of their advertising.

The factory site moved around a bit, judging from the ads and listings in the St. Louis city directories. A new building to house the factory was constructed at 900 Boyle Avenue in 1909. The address is still valid, and from the looks of it, the one-story building could well be the same. Most of the floor space is now unoccupied. I was also able to find their home, located at 241 Selma Avenue in the suburb of Webster Groves. The house is just down the tree-lined street from Webster Groves High School, and Webster University is just a few more blocks away.

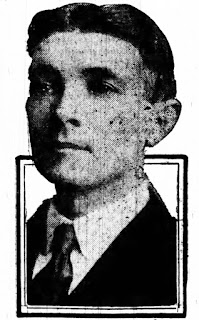

The Victor Automobile Manufacturing Company ceased operations in 1911 due to the premature death of its president, Joseph Harrington. His wife, Julia, later testified that he had been quite sick during the period from 1896 to 1905 or 1906. Nevertheless, his death came unexpectedly and quickly; according to his death certificate he died on May 6 due to bowel obstruction, and had been attended by Dr. C.L. Armstrong for three days. The death certificate also states that Joe was to be buried in Calvary Cemetery. Online searches for the site were unsuccessful, though. I was able to find where Julia was buried (she died in 1930), but nothing for Joe. This is what prompted me to visit Calvary Cemetery.

My plan for the cemetery visit was the height of cunning: find Julia’s grave and then nose around reading the names on nearby stones and hope to get lucky. I knew that she was buried in Section 20, but when I arrived at the cemetery I discovered that it is huge. So I stopped in the office to ask directions. I thought that the mere fact that there was an office to visit was a very positive sign. Also, it was both manned and open for visitors! I went in and asked directions to Section 20. The clerk asked me who I was looking for, and I told him “Julia Harrington.” From his computer he printed out a map of the cemetery showing the sections, a map of Section 20, he identified a name on one of the markers close to the road and nearby Julia’s grave, and then he printed off a sheet of details on Lot No. 1450. On this sheet not only were all the burials in the lot specified, but there was even a sketch to show who was buried where. There was Julia H. Harrington (buried 30 Aug 1930); Francis Hoffmeier, the 1-year old grandson and son of daughter Julia (buried 09 Jan 1933); Joseph J. O’Leary, Julia’s brother (buried 11 Jun 1941); Marguerite H. Anderson, the other daughter of Joe and Julia (buried 31 Mar 1970); Oscar B. Anderson, Marguerite’s husband (buried 07 Jul 1988); and, last but not least, Jos. H. Harrington himself (buried 19 May 1911). Of course they got Joe’s middle initial wrong – it should be F. for Francis – and Francis’s name was also misspelled. It’s a good thing that the cemetery was so well organized, because the headstone was not very helpful. All it has on it are the four surnames Harrington, O’Leary, Hoffmeier, and Anderson.

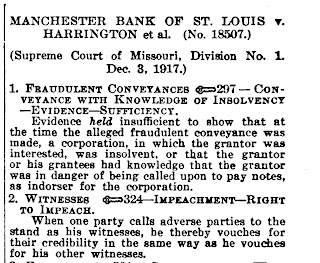

Before our trip to St. Louis I knew at least the outlines of most of the story I’ve told so far. Since our return, the past couple of weeks I wanted to flesh out details and fill in the many gaps in the history. In doing so I stumbled across the record of an appeal to the Supreme Court of Missouri, dated 03 Dec 1917: Manchester Bank of St. Louis v. Harrington et al. (No. 18507).

It seems that when Joe Harrington died in 1911 and the Victor Automobile Manufacturing Company closed shop, the company was unable to cover all of its outstanding debt. The bank was left some $2000 short, and so, being bankers after all, they sued the family to take possession of the house on Selma Avenue. The bank initially won, and the Supreme Court case is the appeal by Julia and her brother Joe to have that decision reversed. In the testimony it comes out just how the Harringtons were able to purchase the Selma Ave. property and, probably, cover costs associated with the car company. This is the reason that I mentioned the name of Julia’s brother, Joe O’Leary, early in this post.

The crux of the matter, to my untrained legal eye, was that Julia Harrington asserted that the bank could not take possession of the house because her brother held the deed. And he held it because over the years he had loaned his sister and brother-in-law thousands of dollars, and he was a secured creditor. As such, he took priority over the bank when it came time for repayments for the car company’s losses. (Please, those of you who do understand the intricacies of the law, let me know how to better state the case.) That begs the question, where did Joe O’Leary get some $14,000 that he could have “loaned” to the Harringtons? By his own testimony, Joe was making only somewhere between $35-$45 per week, of which he sent his sister about $15 a week. From 1898 to the time of Joe Harrington’s death that would have only amounted to a maximum of $10,920.

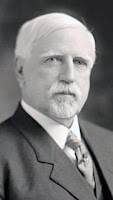

It turns out that Joe O’Leary had another source of income: betting on the ponies. But he wasn’t your typical punter. No, Joe had the inside track. Remember that the father of Joe and Julia was Cornelius O’Leary. Cornelius had a brother named John J. O’Leary, and John had a daughter named Anna. She, in turn, was the wife of a certain John J. Ryan, a man who later in life came to be known as “Bald Jack” Ryan. With a nickname like that, you can probably sense that we’re heading toward the wrong side of the law.

Ryan began his notorious career as a bookmaker, and from there moved on to become a “horseman” or “turfman.” He owned race horses, built race tracks, and ran pool halls to accommodate betting. He operated across several states, from Missouri to New York, and north into Canada. Eventually he became well known enough to the authorities, jockey clubs, and such that he was forced to leave the horse racing business. From there he moved on in 1909 to, what else, playing the stock market. Later he became a speed boat racer and was a partner in a boat-building business that eventually became Chris-Craft Boats. He had a colorful life, and you can read much more about him in a 7-part story entitled The Horseman, written by Joe Ryan.

Joe O’Leary testified that he made thousands of dollars betting on horse races while he was working as an artist in Cincinnati and Chicago. His cousin, Anna Ryan (Bald Jack’s wife) would telephone him and pass on in code the names of horses to bet on. O’Leary never deposited the money in a bank, but left it for safekeeping at Dermody’s “bar” in Cincinnati. This was the source of the money that was supposedly lent to Joe Harrington. In the end, the appeal by Julia and Joe O’Leary was successful, and Julia was able to live out the rest of her life in the house on Selma Ave.

In the years after her husband’s death, the activities of Julia Harrington and her daughters often appeared in the society pages of St. Louis newspapers. The youngest child, Julia Josephine, was sent to spend her final year in high school in Los Angeles, California. There are notices of the girls and their mother traveling to visit friends around the country. One question, though: if, at the time of Joe’s death, the family risked losing their home because of a debt of $2000, on what income did they maintain that lifestyle for the next 19 years? Maybe Joe O’Leary had other cash assets stashed away somewhere?

The St. Louis Post-Dispatch reported on 09 Oct 1921 that the youngest daughter, Julia, left for Los Angeles to attend high school at Ramona Convent, a private school. She spent the holidays in California. As graduation day approached on 18 June 1922, the Globe-Democrat reported that “...she was suddenly stricken with appendicitis last Sunday and an immediate operation was necessary.” Upon return, I found her picture in the newspaper when she was voted Queen of the Armistice Ball in 1923.

Finally, to wrap up a few loose ends: I’ve mentioned that Julia, the mother, passed in 1930. Julia the daughter married John Joseph Hoffmeier (1903-1979) in Cleveland on 3 Jan 1926. At about that time her uncle Joe O’Leary was also working in Cleveland. What a tightly knit family! Julia Hoffmeier had 3 children, and she died in Santa Barbara in 1998 at the age of 94. Joseph Harrington Jr. appears in the 1920 census, but in his mother’s obituary in 1930 he is said to be deceased. I haven’t been able to find any record about what happened to him. Finally, the oldest daughter, Marguerite, married Oscar B. Anderson on 18 Dec 1945 in Phoenix at the age of 46. They had no children of their own, and Marguerite died in 1970, aged 71, in San Francisco.

So ends my tale of the life of Joseph Harrington. I’d expected my trip to St. Louis to be relatively uneventful, but his history turned out to have a few more surprises than I expected. There are still a lot of gaps to fill: what did he study at Mount St. Mary’s and at the Catholic University? What happened to Julia O’Leary’s mother? How about Joseph Jr.? Is any of Joe O’Leary’s artwork still around? I’ll be sure to include an update if and when new information shows up.

References

- Anonymous. 1908. The horseless buggy. The Spokesman of the Carriage and Associate Trade 24(6): 167-182. (The section entitled “The 1908 Hand Forged Victor” appears on page 182.)

- Manchester Bank of St. Louis v. Harrington et al. 1917. The Southwestern Reporter 199: 242–250.