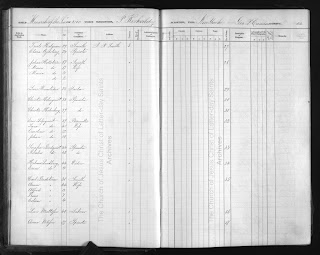

I'm going to focus on a young lady named Clara Björling (also spelled Bjurling). Clara was born in 1840 in Kumla, Västmanland, the eldest of eight children of Jan Eric Björling (1817-1906) and Anna Greta Bergström (1817-1897). Her family name is pronounced something like“b-your-ling.” To put her in context, Clara was the 2nd great granddaughter of Lars Ericsson, the oldest ancestor on the Westerlund line that I've been able to document. To be specific, the line is from Lars Ericsson (1698-1757) to Maria Larsdotter (1753-1824) to Margareta Bjurman (1779-1864) to Anna Greta Bergström (1817-1897) to Clara. She is my third cousin 4 times removed.

In 1842 Clara and her family moved from Kumla to Kila, and six years later to Romfartuna. In 1849 they were back in Kumla for about a year, and then they moved south to the city of Västerås. At the age of 18 Clara set off on her own to find work. The church records say that she went to Stockholm, but in fact she moved south: first to Ringarum in the province of Östergötland, then to Dagsberg, and then to Norrköping. It wasn't until 1860 that she finally found her way to Stockholm where she lived in the quarter of Cerberus (a block of buildings). I haven't found a record of what she was doing for work during this time: she's simply listed as piga, that is, an unmarried young woman. A later family history says that while in Stockholm she sang with the Stockholm Royal Opera. On February 26, 1862 there was a life-changing event: on this day she was baptized in the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. Then, together with Truls Asarsson Halgren, in 1864 she left Sweden to head to Zion, to the new Mormon settlements in the Utah Territory.

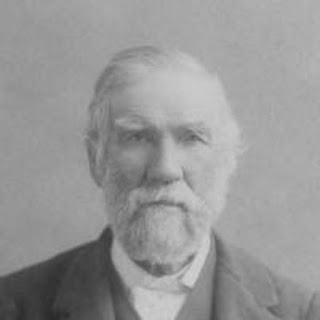

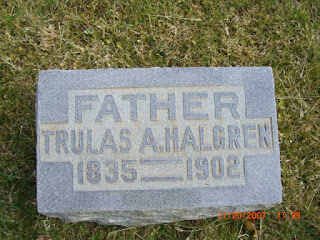

Truls was born on 5 Jan 1835 in Lilla Slågarp in Skåne, in the far south of Sweden. He was a blacksmith by trade. He had been baptized into the LDS church on 26 Aug 1858. These were early days for the Mormon church in Scandinavia, and the state Lutheran church did not look kindly on the competition for souls. Truls was ordained a priest and sent to Torshälla where he was arrested and jailed for proselytizing. After release he continued his work in Gotland for 18 months, and then went on to Stockholm.

From Sweden to America

In April of 1864 Clara and Truls decided to emigrate from Sweden to America, heading to the Utah Territory that had just recently been settled by Mormons. The couple travelled from Stockholm to Copenhagen, and then to Liverpool in England. I haven't found specifics of how they got to Liverpool, but one common path was to sail from Stockholm to Copenhagen, then sail to Lübeck (now in Germany) on the southern coast of the Baltic Sea. A short overland trip from Lübeck to the port of Hamburg, from which a ship would take them down the Elbe River and across the North Sea to the port of Grimsby. From there a train ride would take them directly west to Liverpool (home of the Beatles!).

Bottom: The port of Hamburg in 1875, 11 years after the trip of Clara Bjurling.

In Liverpool Truls and Clara, still unmarried, boarded the Monarch of the Sea for the voyage across the Atlantic to New York. From this point on, although I don't have any records directly from Clara, a number of other emigrants did have contemporaneous diaries or later wrote of the trip in their memoirs. Some of these memoirs were written by people who were in their early teens during the voyage, so it's not surprising that often the fine details of the trip differ, but I think the spirit of the times comes through loud and clear. I've listed some of these sources at the end of the post.

Clara and Truls were not making this trip alone. Far from it: the entire transport all the way to Utah had been arranged in advance by church officials. They were accompanied by 971 other Mormon emigrants aboard the Monarch of the Sea and were led by patriarch John Smith. Each emigrant either paid for the trip up front or, probably more commonly, signed a note promising to repay $60 plus 10% interest to the permanent emigrant fund. The ship, under the command of Captain Kirkaldy, was delayed in port, partly because of the difficulty in taking on acceptable sailors. This problem was caused by the high bounty the United States was paying for sailors to serve in the Navy: this trip was being taken in early 1864 at the height of the Civil War. The ship finally set sail on the 28th of April, 1864.

The Monarch of the Sea was a sailing ship, and so progress depended on the strength and direction of the winds. The wind seems to have been particularly fickle, often very light so that progress was slow, and at other times frighteningly strong. In one case the winds blew so hard that two of the jib beams were broken under the strain, and the sailors struggled to repair them while the ship was underway. The strong winds, of course, led to seasickness among the passengers. One young girl recorded that her father actually lashed her to the ship in the hold because it was rocking so severely. She also recalled an occasion in which her uncle was just sitting down to a meal of peas when the rolling ship sent him and all the food flying, and he was soon on the deck sliding around in the middle of his dinner.

Meals were a problem. Each emigrant received a ration of oatmeal, rice, peas and meat (bacon and corned beef), occasionally some potatoes, coffee and tea. As the voyage progressed the meat, shall we say, "ripened," so much so that one man claimed that when a barrel was opened it could be smelled the length and breadth of the ship. It was so bad that he thought the barrels must be ready to explode from the pressure inside. Even beyond the quantity and quality of the rations, though, a big problem was that the ship was simply not equipped to accommodate cooking for nearly a thousand people. There was a single pot where each family, in turn, could have their food cooked. Often it came out scorched, but no one was in a position to complain.

There were more severe forms of illness on the trip than seasickness. The details are sketchy, particularly since the information comes from the passengers themselves and not doctors. Speculation of the nature of the disease(s) on board included measles and scarlet fever. The impact of the diseases was borne by the children. The reported numbers vary, but somewhere between 42-66 children and one adult man died and were buried at sea. Even assuming the lowest number of deaths, this is heartbreaking. But also during the trip 14 couples were married. One of these was Clara Bjurling and Truls Halgren. The family history says that, because so many people were confined to their bunks because of seasickness, the captain asked Truls and Clara to get married immediately so that they could be moved into the the married quarters and open up space where they had been berthed.

On 3 June, 1864 the weary travelers reached New York after a voyage of 37 days. There they were processed at Castle Garden (the predecessor of the more famous immigrant reception at Ellis Island). This consisted of a medical check and recording of names. I can't imagine this was done too carefully: there were over 900 immigrants on this ship alone, and by the end of the day they were already on their way out of New York on the next stage of their trip.

New York to Nebraska

On the evening of June 3 the company boarded a steamer to take them up the Hudson River to Albany. They arrived there about 4 a.m. the next day and then boarded a train to start west. The train pulled 22 passenger cars and traveled parallel to the Erie Canal. They made it to Rochester at dawn, June 5, and by 1 p.m. had reached Buffalo. There they crossed the Niagara River on a steamer and reboarded a train on the Canadian side of the border. By the next day they had made it to Port Edward, crossed the Detroit River, and then continued across Michigan. The entourage arrived in Chicago at 8 p.m. on Tuesday, the seventh, where they spent the night.

The next leg of the journey was from Chicago to Quincy, Illinois. After crossing the Mississippi, the train continued across Missouri, first to Palmyra, then to Brooksfield, and finally to St. Joseph on the Missouri River. Most of the trip from Albany to Quincy was not made in passenger cars. Rather, the emigrants were loaded into freight box cars and sat on wooden benches without any back support. After crossing the Mississippi they were again confronted with the prospect of continuing in the freight cars, and at this point they mounted a small rebellion:

"Here our company refused to travel that way and we had to wait till the next day. We had no shelter for the night and no access to our bedding. We went into the woods and the weather being fine, and by the use of shawls and overcoats we made ourselves tolerable comfortable. I think it was the most comfortable night spent for a week. The following day we were furnished regular cars, and we traveled on to St. Joseph. I think now it may be that the railroad company had been furnishing cars for the transporting of soldiers to battlefield and that the freight cars, fitted up with temporary board seats were such as had been for such used transportation, and perhaps on this account was unprepared to furnish cars for an extra train as was required for our company." (Reminiscences of H.N. Hansen)

After a week, the saints reached St. Joe. "St. Joseph was not much of a place at the time when we arrived there. We were dumped off near the Missouri River on the sand. If there was a depot we were not taken to it. Perhaps if there was one, it would have been too small to accommodate our crowd. Here we boarded a steamer which slowly paddled us up the Missouri River to a place called Wyoming, about seven miles above Nebraska City where we arrived about the middle of June. This was the place selected from which we were to begin our tedious journey across the plains." (Hansen)

Walking from Nebraska to Utah

The last, long leg of the trip was made on foot. This was organized by the church. Wagons pulled by teams of oxen had been sent out from Utah in the spring to meet the emigrants and lead them back to Salt Lake. The expedition in which Truls and Clara travelled was led by Captain Isaac A. Canfield (1818-1891). After six weeks roughing it along the Missouri, the expedition started off on 27 July 1864. It consisted of about 218 people, 30 teamsters, and about 50 wagons. The expedition had two purposes: to bring the emigrants to Utah, but also to pick up goods for merchants and cooperatives in Salt Lake City. In fact, each emigrant was allowed only 50 pounds of goods including bedding.One of the other impacts of the ongoing Civil War, beyond the availability of passenger cars for the train, was that many of the Army units were called back from the West to take part in the hostilities back east. A little more context might be helpful here. The construction of the transcontinental railroad had just begun, but would not be completed for another 5 years. However, telegraph lines had been strung from the Atlantic to the Pacific, so as the expedition proceeded they were able to send news of their progress ahead to Salt Lake City. And here's a little reminder from those Social Studies classes you may have dozed through back in the day: in 1862 the Homestead Act was signed into law. This allowed any American to claim up to 160 free acres of federal land. This impacts our travellers because these federal lands were not empty: no, they were the homelands of numerous Indian (Native American) tribes. Clara, Truls and the rest of the expedition were to travel through territory occupied by the Cheyenne, Arapaho, and Sioux tribes. The influx of homesteaders and the departure of soldiers were two elements that opened the door to armed conflicts.

There are two records of their progress from emigrants, and this combined with newspaper reports of the expedition's progress make it possible to track Clara and Truls in their journey from Nebraska to Utah. Initially the company followed the North Branch of the Platte River to its confluence with the Sweetwater River. Along the way they crossed the rivers several times. These rivers are wide but very shallow, only reaching up to the axles of the wagons. Early after they began, they ran right into evidence of the Indian resistance. Here is the account of Hansen:

"One day we passed a house right by the road side, it was burning slowly, and about two or three rods from the house laid a man dead presumably the owner of the place having being killed by the Indians that same day, perhaps not an hour before we arrived on the scene. I do not know whether anyone examined to see if he was shot or where, or how he was killed but we saw that he was dead. I, like boys would be likely to do ran with the rest to see the sights.

The ground was dusty where the corpse lay, and it was so besoiled that it was difficult at first glance to tell whether it was a white man or an Indian, but of course by a little closer examination it was seen to be the body of a white man and we took it for granted that it had been the owner of the house which now was burning. The Indians had taken out of the house what they wanted and then fired it. They had emptied the feather beds and the contents were flying round by the breeze. They evidently thought they had no use for feathers, their custom not demanding so soft a bed. Whether the rest of the family was murdered and laying somewhere in the weeds or the burning house, or if any of them had been carried away by the Indians we did not learn, and I do not know if any gave the matter serious thoughts at that time."

The accounts of Rev. Hansen and others record numerous deaths along the way, likely a combination of sickness and fatigue. Fortunately, the trek started early enough that they were not trapped by snows in the mountains as had some earlier expeditions to Utah. There were periods when water and firewood were difficult to find, and as they traveled west the forage for the oxen gradually dried out. Wagon wheels broke down, wagons themselves were overturned, the oxen stampeded on one occasion with one breaking a leg and two others had their horns broken off. Despite these setbacks, the company made good progress and finally arrived in Salt Lake City on 4 Oct 1864.

Truls and Clara Halgren settled about 40 miles north of Salt Lake City in Ogden, Utah. They had eight children: Asser Theodore (1865-1875), Ellen Wilhelmina (1866-1923), Anna Magdelena (1868-1944), Alma (1870-1871), Clara Sophie (1873-1874), Olivia Victoria (1875-1878), Joseph (1877-1951), and Otelia (1879-1944). The portrait of the family below shows Clara with baby Joseph on her lap, so this was taken sometime around 1878-1879 depending on how old you think Joseph is and whether Clara was already pregnant with Otelia. Truls was twice called upon by the church to missionary work, once in Sweden and once in Finland. His biography and portrait are included in the book Pioneers and Prominent Men of Utah, published in 1913. Truls passed away in 1902, and Clara in 1910. They are both buried in Ogden.

As far as I'm currently aware, Clara was the first descendant of Lars Ericsson to emigrate to the United States. The wealth of records maintained and made available by both the church and Clara's descendants made it possible for me to much better understand and, to a limited extent, relive her experiences traveling across the world in the 1860s. I hope that I've been able to give you a taste of it as well. I came away from this story with a great deal more appreciation and admiration for their tenacity and ability to withstand the hardships that these people suffered in order to restart their lives in the American West.

Some source materials

Note: I have not directly consulted the hard copies of these journals and manuscripts, only that which is available online. Therefore the citation details may not be entirely accurate.- Mormon Migration.

- Do you remember? The lives of Joseph Halgren and Sara Alice Aldous As remembered by their children.

- Finlinson, G. 1974. George Finlinson family, 1835-1974, comp. by Angie F. Lyman. Privately printed.

- Hansen, H. N. 1971. An account of a Mormon family's conversion to the religion of the Latter Day Saints and of their trip from Denmark to Utah. Annals of Iowa, summer 1971: 722-28, and fall 1971: 765-67.

- Sprague, M. O. Reminiscences. Utah Pioneer Biographies 27: 51-52.

No comments:

Post a Comment