In a short biography of one of Jeremiah’s sons (Bartholomew), I learned some details about his early history. Jeremiah came to California in 1855 at the age of 25 or 26, about six years after the famous Gold Rush. Initially, he worked as a miner in the northern part of the state. He became an American citizen on 24 Sep, 1856, with the naturalization taking place in Shasta County. (The county seat is the town of Redding, a town we will revisit a bit later). He moved to Santa Cruz County in 1857 and settled on land along the Pajaro River, approximately 3–4 miles east of the modern town of Watsonville.

One of the first experiments in farming in the area around Watsonville – the first, that is, by the immigrants coming from the eastern part of the country – was to plant potatoes. This experiment turned out to be wildly successful, so much so that an oversupply of the crop caused the price to crash, and that led to the devastation of the farms. Recall, that this was in the time before the completion of the transcontinental railroad, and so the producers were limited to the local market. Following that crash, much of the land was planted in grain, including that owned by Jeremiah.

Jeremiah Driscoll married Johanna Hickey, another native of County Cork, and together they had nine children. He died on 11 Apr, 1884 at the age of 55 (reported in the newspapers as 53). In the account of his death, published in the Santa Cruz Sentinel, it was noted that “[b]y his own energy and industry Mr. Driscoll acquired one of the best farms in the county.” His estate included land holdings of 350 acres, valued at the time as $30,000. I’ve translated 1884 dollars into 2021 dollars, the equivalent being somewhere over $800,000. I don’t think simple calculations based on the rate of inflation adequately capture the value of land in California in today’s market. All told, I think we can agree that Jeremiah left an estate worth somewhere north of a million dollars.

Jeremiah’s legacy included more than valuable farmland. His children achieved fame that extended beyond the Pajaro Valley, and for the rest of this post, I’d like to focus on one of them, his daughter, Julia.

The first hint of what was to come, the first foreshock, came at 5:12 a.m. on the 18th of April, 1906: nineteen minutes before sunrise. Less than a minute later, the San Francisco Earthquake hit. The magnitude 7.7–7.9 quake and its aftermath of fire resulted in more than three thousand deaths, 225 thousand injuries, and an estimated $400 million dollars in damage. In today’s dollars, that’s roughly $11.6 billion.

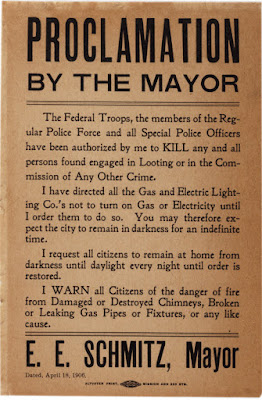

On the day of the quake, a proclamation was posted in the newspapers and around the city by the Mayor, Eugene E. Schmitz:

I’m not sure if anyone was actually shot on sight, but the aggressive, take-charge attitude earned Schmitz publicity around the country and around the world.

Schmitz was the son of a German father, Joseph L. Schmitz, and an Irish mother, Charlotte Hogan. He was born in 1864 in San Francisco, and he grew up to be a musician and composer, a violin player. That wouldn’t seem to be the typical route into politics, but in San Francisco at the turn of the 20th century labor relations were one of the hot topics. Gene Schmitz was elected to be President of the local Musicians’ Union.

As the leader of one of the city’s labor unions, not to mention his charisma and good looks, one of the local political “bosses,” Abe Ruef (1864-1936, photo at right), tapped Schmitz to run for mayor on the Union Labor Party ticket in 1901. In a three-way race, Handsome Gene won election to his first two-year term. He was then re-elected in both 1903 and 1905.

By this time of his third election, rumblings of trouble began to be heard: not the earthquake, but rumblings about political corruption. The pursuit of allegations was continually stalled at the local level, so the editor of a local newspaper appealed to President Theodore Roosevelt for help. Through Roosevelt’s intercession, the sugar baron Rudolph Spreckels helped to bankroll $100,000 for investigations. I know that I shouldn’t impose modern standards on the actions of people more than a century ago, but the idea of a private citizen providing money to the government to pursue criminal allegations sounds like a recipe for all sorts of shenanigans. Maybe the people with the deep pockets are just more discrete these days.

The investigation, led by William Burns of the Secret Service, was underway on the fateful day of the earthquake. The main thrust was corruption, and one of the more salacious elements of it concerned the so-called “French restaurants.” To be fair, these establishments did serve food to customers on the lower floors, but upstairs the world’s oldest profession was the real order of business. The restaurant proprietors needed to obtain a liquor license from the city, but would often find their applications denied. Denied, that is, until they could schedule a meeting with Boss Ruef and make a contribution of $5,000 to the cause. Then, amazingly, Mayor Schmitz would make an impassioned plea to the police, and the liquor license would be approved.

The intensity of the investigation waned in the immediate wake of the earthquake. After the city stabilized, Schmitz surprised everyone by leaving for a tour of Europe in October of 1906. His expressed purpose was to visit and consult in the capitals to develop ideas about how to rebuild from the ashes. You might think that he was just skipping town in order to avoid arrest and prosecution. But when the indictments did come down, he dutifully returned to San Francisco to face trial.

That was a tease. Before telling you about the outcome of the trial, let me explain you why I’ve included Mayor Schmitz in this story.

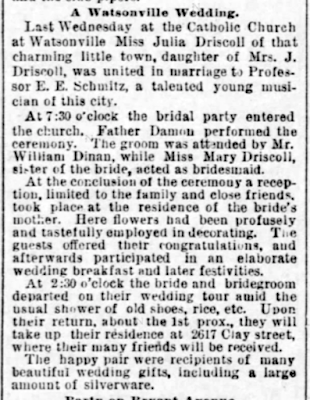

It turns out that Mayor Schmitz, “Handsome Gene,” was married to the daughter of Jeremiah Driscoll, a young lady named Julia A. Driscoll. Newspaper reports tell us that Julia was educated in the public schools of Watsonville and San Francisco. The San Francisco Examiner described her in 1901: “She is eminently American – clear-headed, common, sensible, wide awake, unaffected, sincere, quick-witted, refined, practical. She is of the type that cannot be too many – the home-keeping, domestic woman, who is not swamped in her domesticity; that pleasant American type of woman who can look well to the ways of her household and still permit herself the wider range into the ways of the world.” (The San Francisco Examiner, 07 Nov 1901, page 2.)

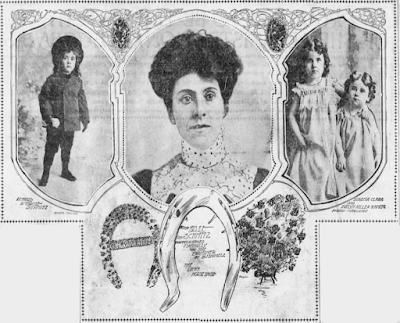

When Schmitz was first elected, the couple had three children: Eugenia Clara (born 1892), Evelyn Heller (born 1894), and Richard Ambrose (born 1896). In the interview published in The San Francisco Examiner in 1901, Julia explained why she had been certain that her husband would win the election:

"Somehow," she says, "I felt confident from the very first. Mr. Schmitz had never been in politics. He had gone along quite contentedly, never thinking of anything beyond success in his profession and in a business way, perhaps, yet, when the matter was first broached and the nomination offered to him, and he came home and told me about it I felt he would be elected, and through the campaign I never lost my belief. Through all his anxieties of the campaign I tried to keep up his confidence and hope with my own, for I never wanted him to feel for a moment that he wouldn’t win."

And what kind of a Mayor do you think Mr. Schmitz will make?

"Why," answered Mrs. Schmitz, "I have always felt that he had exceptional ability, that opportunity would bring it out, and," here Mrs. Schmitz smiled a smile of wifely pride, "if Mr. Schmitz makes as good a Mayor as he has made a husband, he'll make a very good Mayor indeed!"

Unfortunately, that didn't turn out as well as Julia had hoped. Abe Ruef "copped a plea" for which he received immunity from most of the charges against him in exchange for his testimony against Schmitz. On 14 Jun 1907, Mayor Eugene Schmitz was convicted of extortion. Ruef was convicted of bribery in 1908, and he was sentenced to 14 years in San Quentin, a sentence he finally began serving in 1911. Schmitz was down, but not out, though. He appealed his conviction and won. However, he was tried again, this time for bribery. At the second trial Ruef refused to testify against him again, and Schmitz was cleared.

Schmitz ran for the office of Mayor twice after his brush with the law, but he never regained the post. He was elected to the San Francisco Board of supervisors where he served from 1921 to 1925. He never gave up on his music. In 1912 he was working on the music for a operetta entitled "The Maid of San Joaquin." The Pacific Coast Musical Review wrote that "...its object is to depict the early California mining life in a manner more realistic and tasteful than has been done in the "Girl of the Golden West." In hindsight, it was probably asking a lot to outdo Giacomo Puccini whose La fanciulla del West" had premiered at the Metropolitan Opera in New York in 1910 with Enrico Caruso in the cast! The Review also stated, "There is no doubt that the work contains exceptional merit both from a musical and literary point of view, and in these days of comic opera stagnation, or even light opera famine, this work ought to find a place in the repertoire of the leading American companies." Apparently, producers on the East Coast were not as enthusiastic, and I could not find evidence that the operetta ever saw the light of day. However, in his obituary it was written that he had produced his own opera in New York. Perhaps it did have an audience, after all.

Eugene Schmitz died on 21 Nov, 1928, in San Francisco. He never regained the previous heights of his career, and in his later years he had shaved off the beard that gave him such a swashbuckling image. Eugene and Julia lost their son, Richard, in 1914 following an operation for appendicitis. Schmitz was in New York at the time, working on getting his opera staged. The two daughters lived long lives. Eugenia became a Dominican nun in 1914, taking the name Sister Mary Isabel. She retired as a secondary school teacher after 47 years of service, and was honored on the occasion of her 60th anniversary in the order. Evelyn lived to the age of 92. As far as I know she never married, and I have not found much information on her life. Julia, herself, passed in 1933 at the age of 68. It was reported that she took her husband's legal troubles very hard, and her health suffered for it.

I hate to end the post on such a sad note, so I would like to offer something to celebrate the life and liveliness of Julia (Driscoll) Schmitz and her daughter Evelyn. While researching for this post, I found some images of Eugene that had been posted on the web by the San Francisco Public Library. One of these showed him together with his wife and daughter Evelyn, apparently posing for photos during an election. The image on line is of only fair quality, but it inspired me to inquire at the library whether they had other pictures of Schmitz's family. They did! Not the greatest quality, but images that help to animate the facts that I was able to glean from newspapers and other sources. These images, apparently, have never been published before. I offer them with a nod of appreciation to the lives of Julia and Evelyn Schmitz.

I have another story about a descendant of Jeremiah Driscoll. But this post is already long enough, so I'll save it for next time. But here's a teaser: this child had an even greater influence than the Schmitz family, an influence that I think a good number of readers can identify with. Stay tuned.

No comments:

Post a Comment