My goal in this post is to pick up with another of the sibs of Timothy Driscoll, his brother Jeremiah (1829-1884). In my last post I described the colorful history of one of Jeremiah’s daughters, Julia, who was the wife of the notorious mayor of San Francisco, Handsome Gene Schmitz. Jeremiah was Tim’s older brother, baptized in early 1829, so either born that same year or possibly late in 1828. I’m not sure when he emigrated from Ireland to the U.S., but he was naturalized in 1856 in Shasta County, California (so, he was about 28 years old at the time). He later moved south and settled in the Pajaro Valley near the coast in central California, and I’m fairly certain that it was in California that he married another emigré from County Cork, Johanna Hickey (1833-1920). Together they had nine children: Mary Ann (1860-1946), John Joseph (1861-1955), Timothy F. (1863-1882), our friend Julia (1864-1933), Jeremiah C. (1866-1951), Richard Francis (1869-1934), Daniel Ambrose (1872-1953), Bartholomew Leo (1873-1944) and Margaret L. (1877-1853).

Jeremiah seems to have been a fairly successful and prominent man in the valley. His death was noted in the Santa Cruz Sentinel: “By his own energy and industry Mr. Driscoll acquired one of the best farms in this county [Santa Cruz County]. … Father Francis Cordina performed the funeral rites. In the obituary he spoke of the many virtues of the deceased, whose piety and unostentatious charity were well known to the clergymen of Pajaro Valey. … Mr. Driscoll’s family have the sincere sympathy of this community, and he shall be missed here and is much regretted by all….” There are more details and even a poem accompanying the article. This is a fairly elaborate obituary for 1884, and I think it probably attests to the status of Jeremiah in the community, the wherewithal of his family for such an extensive elegy, or a combination of the two.

Actually, I know fairly little about Jeremiah. My focus here will be on one of his children, a person that I’m certain is already familiar to many of you. This is his son Richard. In fact, I’d heard of him – or at least his legacy – for years without realizing it. Every time I walked into the grocery store and went through the produce section, there was his name: Driscoll’s Berries. I never made the connection until researching this branch of the family tree. The Driscolls of berry fame are the descendants of Jeremiah.

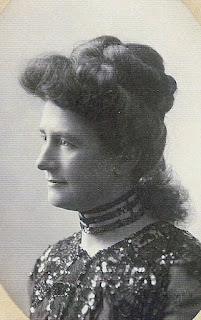

The story of Driscoll’s Berries is well documented, both in print publications and on the web. Richard Driscoll married Margaret Olive Reiter (1875-1965) on November 27, 1889 in Castroville, California. She was the daughter of Joseph Nei Reiter (1833-1920) and Philomena Catherine Meyer (1845-1913). Her mother, surprising to me, was born in Cleveland, and her father came from Alsace Lorraine in France (now Alsace-Moselle, but at that time this was disputed territory between France and Prussia). In their book A History of the Strawberry from ancient gardens to modern markets, Stephen Wilhelm and James E. Sagen have an extensive appendix (69 pages long) recounting the history of the California strawberry industry. My summary will build upon theirs.

I mentioned Dick Driscoll’s wife, Ollie, because her family plays a central role in the story. Somewhere between 1900 and 1902, her sister Louise visited friends who lived on the Sweet Briar ranch in Shasta County, near Redding (mentioned in my last post, Shake, Rattlee and Roll). There she was served strawberries for breakfast that immediately caught her attention as being better than any of the varieties that were being grown in and around Watsonville. When she returned, she reported this to her brother, Joseph Edwin (Ed) Reiter and her brother-in-law, Dick Driscoll. Reiter and Driscoll had been growing berries since at least 1896. They quickly established a relationship with ranchers in Shasta County to grow this new variety (new to them, at least) that was called Sweet Briar, after the original ranch. Strawberry production turns out to be a fascinating subject. The plants were grown in the mountains, and then dug up and shipped down to the coast to be replanted. After a year of growing in their new home and sending out runners, the plants would then be allowed to produce fruit. Following that, though, the plants would regress and fail to produce new runners. Therefore, they had to be removed and replaced with new plants from Shasta County. This is still largely the method used, although newer varieties don’t require that intervening year where no strawberries would be produced. The nursery operations take place at higher elevations and cooler temperatures, while fruit production takes place along the coastal plain.

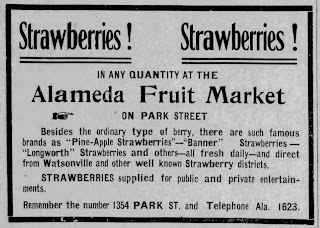

It is one thing to have a good product, but quite another to translate that into sales. The primary market for strawberries produced in the Pajaro Valley was the San Francisco area. Reiter and Driscoll would ship their berries north in crates, and around each crate they would tie a blue paper ribbon with a picture of a red strawberry. For buyers, this ribbon identified the superior Sweet Briar fruit. Because of this association of the berries with the ribbon, the name of the variety changed, becoming known as the Banner variety. The first newspaper ad that I was able to find in the Bay Area newspapers using the name “Banner” was printed in mid-May of 1911. This variety was so popular that it displaced all the others that had earlier dominated the market.

Ed Reiter and Dick Driscoll basically had a monopoly on Banner strawberries up until about 1912. After that, other ranchers could see their success and quickly moved to obtain their own plants. Driscoll shifted his operation to new ranches, particularly trying to avoid fields that had previously been used to grow strawberries. Although the details were poorly understood at the time, strawberry plants are susceptible to a number of fungal and virus diseases. Some of these can persist in the soil for several years. This was not unique to Banner, and it continues to be a pressing concern today. Therefore, even now before strawberries are planted, the soil is fumigated to reduce or eliminate these problems.

As a quick aside, strawberry farming is a labor-intensive operation. In these early years when Dick Driscoll and Ed Reiter were achieving prominence, much of the labor was performed by Japanese sharecroppers. The “bosses” would provide the land and plants, and the sharecroppers would grow, care for, and harvest the fruit. At the end of the day, the profits were generally evenly split. Of course, much of this mutually beneficial relationship was upended with the Japanese internments during World War II.

Dick and Ollie Driscoll had six children: Richard Oliver (1900-1971), Edwin Francis (Ned, 1902-1981), Agnes Marie Louise (1905-1996), Donald Joseph (1908-1986), Kenneth Leo (1911-1936), and George Vincent (1914-1958). As noted earlier, Dick passed in 1934 and Ollie in 1965.

Of all the story lines to pick up here, one of the most important for the success of Driscoll’s as a company starts with Dick’s son, Ned. Banner strawberries had been a tremendous success for the partnership of Dick Driscoll and Ed Reiter, but after only a few years most if not all of the ranchers in the Pajaro Valley had begun growing the variety for themselves. After twenty years of large-scale production, though, Banners began to be hit by diseases. By 1950 it was entirely gone. To continue to take advantage of the climate and soils of California for strawberry production new varieties were needed, varieties bred to withstand the various wilts and viruses that inevitably spell doom for the plants. Development of such varieties, though, takes time, money, and the acumen of horticulturalists to recognize commercially valuable traits and try to combine them in a single plant through careful breeding. But if, after all of that effort, everyone and his brother could plant the same variety and compete on the market, it might be impossible to recoup all of that investment.

Ned Driscoll was involved with early experimentation with varieties that had been produced by researchers at the University of California at Davis around 1937. These varieties, having been produced by an arm of the state were available for all growers to use. Ned pioneered the adoption of winter plantings; previously the stock brought down from the mountains was planted in March. This eliminated that year of establishment that earlier growers had needed. Further, in 1944 he, together with his brother Donald, their cousin Joe Reiter, and three others, established The Strawberry Institute of California. The organization was devoted to the development of new and better varieties, research on cultivation, and support for all grower members. They achieved a bit of a “coup” when the two leading researchers at UC Davis resigned to go to work for the Institute. In 1958 they patented their first variety, Z5A. According to Baum (2005), this made Driscoll’s “…the premier California grower-shipper, a position they still retain.”

Today, the company originally founded by Dick Driscoll and Ed Reiter in 1904 is still privately held, with an estimated global revenue of $3.6 billion in 2018. They have expanded their product line, producing not only strawberries, but also raspberries, blackberries and blueberries. They have also moved beyond – but not out of – California, with both growing and marketing efforts worldwide. The plastic clamshell box that berries are now sold in: that’s another Driscoll’s innovation. Today the company is the largest berry supplier in the U.S., and is led by J. Miles Reiter, the grandson of Ed.

In doing the research that led to this post, I’ve made contact with several of the descendants of Jeremiah Driscoll, both from California (at least originally) and in West Cork. Some have told me that they remember the time when the relatives from California would regularly come back to Ireland for a visit. Unfortunately, my immediate family was not part of that. My grandmother was an only child, and her mother – Johanna Driscoll – died just shortly after giving birth to her. But there were other Driscolls that came to live in Oswego. I wonder if they have retained links with their cousins.

Finally, let me close with a bit of a confession. Here in central Ohio (as in much of the rest of the country), if you drive through the rural areas you’ll see mile after mile of corn. Those fields will also have signs posted, telling you the variety of hybrid plant that’s being grown. For many years it has seemed somehow “wrong” to me that farmers could be sued if they retained some of the seed from the previous year’s crop to plant in the spring. (Not that hybrid seed would be much good!) But in learning of the costs and effort it takes to develop new strawberry varieties, I think that I’m a bit more sympathetic to the idea of patenting plant varieties.

I have another prejudice that this story is undercutting. I’ve long looked down my nose at commercial strawberries. I remember, or I think I remember, picking wild strawberries and how intense their flavor was. You just never get that in a store-bought fruit, do you? But perhaps this is just my own nostalgiac notion, and they were never really that good. I must admit that I’m developing a new taste for the produce in my local market.

Sources

- Baum, H. 2005. Quest for the perfect strawberry. iUniverse, Inc., New York.

- Driscoll’s Wikipedia page: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Driscoll%27s

- Driscoll’s Berries website: https://www.driscolls.com

- Goodyear, D. 2017. How Driscoll’s reinvented the strawberry. The New Yorker, 14 Aug 2017. https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2017/08/21/how-driscolls-reinvented-the-strawberry/amp

- Wilhelm, S. and J.E. Sagen. 1974. A history of the strawberry from ancient gardens to modern markets. University of California Division of Agricultural Sciences.