To briefly recap, The Butcher of Kansas City began with the search for a Swedish emigrant to America named Carl Victor Barthelsson. This Carl Victor, a butcher by trade, was born in 1849 in the Swedish city of Västerås. According to church records, in 1884 he left the town of Karlstad and was never heard from again. My earlier post then veered away to follow another Carl Victor, this one born in 1862. Following that trail led eventually in two directions, one to Magalia, California where his son, Harold, died in 1983, and the second to Scarsdale, New York where Harold's first wife, Joyce (Holloway) Barthelson founded the Hoff-Barthelson School of Music.

At the end of the story, though, we were no closer to figuring out whatever happened to the original Carl Victor. Let's stop here for just a minute, because I can see that with more than one person with the same name, then this story might become pretty confusing. So from here on, when I use the name Carl Victor, then I'll add in parentheses which one I'm referring to. So far we have Carl Victor (Kansas City) and Carl Victor (Karlstad). These are definitely two different persons - uncle and nephew. Also, I'll try to be consistent, but in the records the spelling of the names varies quite a bit: Carl vs. Karl vs. Charles, Victor vs. Viktor, and Barthelsson vs. Bartelsson, etc.

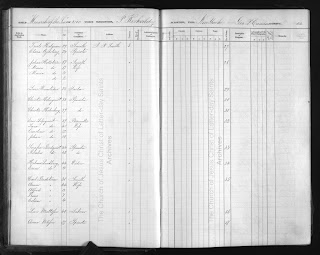

When Carl Victor (Karlstad) departed Sweden he left behind a wife, Anna Christina Eriksson (1840-1922), and three children: Victor Emanuel (1873-1942), Carl Johan (1875-1939), and Herman Mathias (1879-1961). At the time he left for America in 1884 these children would have been 11, 9, and 5 years old. The fate of Carl Victor (Karlstad) in the New World lingered as a mystery, and to her dying day Anna Christina was listed in the church books as a “wife” (hustru) and not as a “widow” (änka). Ann Meyer Nordström, the granddaughter of Herman Mathias, told me that in 1902 her grandfather traveled to America looking for his father. We don't know if he was following any real leads or not, but apparently he came back without solving the mystery.

In a way, though, the mystery of this missing butcher was all the more intriguing because there are American records that seemed to be very suggestive. There is a record of the birth of a child with the magnificent name of Oscar James Napolien. He was born in Chicago to parents Carl Victor Bartelson and Augusta Jenson (Cook County, Illinois Birth Certificates Index, 1871-1922). I first learned about this, our third Carl Victor Bartelson, on the Message Board service at ancestry.com. In 1999 – nearly 20 years ago! – a user named joycemount posted a series of messages in a search for her great grandparents. Here are most of the facts that she laid out, copied from her messages:

I am looking for my great grandparents, Karl Victor Barthelson, born in Stockholm. As I understand it, there is a county of Stockholm, as well as the city. I have no idea what parish he was born in, but he emigrated to the United States about 1880. He entered into New York, then moved to Chicago, where my grandfather, Oscar James Napolien Barthelson was born in 1882. Then they moved back to New York, where other children were born.

My grandmother was Augusta Johnson (Jenson?), she was born in Varmland. We don't know if she and Karl were married when they came to the U.S., or got married here, I'm not able to locate any marriage records so far.

We've been searching for him for about 12 years now, with no success, so would appreciate any help you can give us. (16 Apr 1999)

Another user on ancestry.com pointed out the records for the Carl Victor from Kansas City to which Joyce replied:

As I told you, Victor Barthelson [=Carl Victor (Kansas City)] came to US a little later than my great grandfather, Karl Victor, [Chicago] as my grandfather was born in Chicago in 1882.

I know they were meat cutters, and I'm sure that's why they went to Chicago, with the stock yards there, and there had to be work. (17 Apr 1999)

You can see information in these snippets that both support and undermine the idea that the Carl Victor (Chicago) is our missing man, Carl Victor (Karlstad). On the plus side, we have the name Barthelson (however you spell it). I don't mean to imply that the name is all that unusual, but it's definitely much less common than other Swedish patronymic surnames like Johansson, Andersson, Larsson, etc. Also, Joyce's great grandfather was a meat cutter, the same profession as our lost Carl. I also find suggestive the claim that Augusta was from Värmland because the province from which Carl Viktor (Karlstad) emigrated was Värmland. And beyond these messages, if you follow the records of Carl (Chicago) through time you eventually find that he died in New York City in 1906 at the age of 57. This would make his year of birth 1849 (plus or minus), and this agrees with Carl (Karlstad).

But there's a big problem with this hypothesis: Carl (Chicago)'s son Oscar was born on 3 Dec 1882. This is more than a year before our original Carl Victor (Karlstad) was documented leaving his home parish. Also, Carl Victor (Karlstad) wasn't born in Stockholm, but in Västerås. One other negative piece of evidence comes from the New York census in 1905 in which Carl (Chicago) was estimated to have been born in 1851. That's off by 2 years.

Most of these points are fairly soft, but the one that really blocked me from concluding that Carl (Karlstad) and Carl (Chicago) were one and the same was the birth date of Oscar. If Carl Victor (Karlstad) didn't leave Sweden until 1884, then we must be dealing with two different people. By the way, this is not a case of misinterpreting the church records: the date is clearly written, 1884. So this discrepancy seemed like a damning piece of evidence. There is one possible way out the dilemma, though. What if the date, 1884, was not literally when Carl Victor (Karlstad) left for America, but rather that was the date when the parish priest finally gave up hope that a wayward husband would ever return to his home and family?

To give that idea some credence we could, in theory, look for several different kinds of records. We could try, for example, to find a manifest from the ship that took Carl Victor (Karlstad) from Sweden to America. However, the only such record in the emigrant databases is the 1884 date (and this is derived directly from the church records). No one yet has found a passenger list with any likely candidate. Similarly, no one has yet found a record of entry into the United States, even accepting Joyce's account that he came into New York. On the other side of the record gap, in Chicago, I've not been able to find a marriage record in the Cook County database either. In fact, the oldest record that we have for a likely candidate is the birth record of Oscar.

I never had the chance to ask Joyce Mount directly about this head-scratcher because she passed away in 2010. However, I did get in contact with her sister, Diane Aldrich, who is also interested in the family history and solving the problem. This was a search that had been stymied since at least 1987: one family in Sweden that could not find their relative in America, and an American family that could not trace their ancestor back to Sweden.

Finally, the penny dropped: could DNA help to solve the question?

The Barthelson cousins that I'd met in Sweden are my 3rd cousins once removed. That means that our most recent common ancestors were Per Barthelson (1814-1858) and his wife Kjerstin Persdotter (1814-1888). That would be 5 generations back for me, and four generations back for the cousins. At each generation the amount shared DNA between two relatives is reduced on average by 50%. You can do the arithmetic: would there be enough shared DNA after 4-5 generations to document a relationship that, on the basis of the paper trail, we're next to certain about? As it turns out, there is, but it's not so much that it's obvious. Ann has had her DNA tested on the ancestry DNA platform, as I have. The company then estimates our relationship as 5th to 8th cousins, and rates its confidence in that estimate as moderate. Without the documentation, I wouldn't have paid any attention to that estimate. Note also that their estimate is off by at least a generation or more. That's just the random nature of inheritance. When a father contributes a section of DNA to a child, does the child get their paternal grandfather's or their paternal grandmother's DNA from their dad? It's largely random. However, there's one way that you can increase the odds of finding meaningful DNA relationship estimates, and that's by getting samples one, two, maybe even three generations (!) before you. When we compare the DNA sample that my Aunt Phyllis (my father's sister) submitted – thanks again for that! – her relationship with Ann is estimated as 4th – 6th cousins with high confidence.

The next question, then, is: have any of the descendants of Carl Victor Barthelson (Chicago) had their DNA tested? When I asked Denise, the answer was yes. Both she and her son, Sam, had submitted samples to 23andMe. I'd also tried that testing service, so I logged on and looked at the DNA Relatives part of the website. To my shock, Diane's name showed up on the very first page! 23andMe estimates our relationship as 3rd to 4th cousins, and that we share 1.17% of our DNA. That may not sound like much, but actually it's on the high end of the range that you would predict for 3rd cousins 1x removed. So that pretty much sealed the deal for me: I'm related to both Diane and Ann through my 3rd great grandparents. Now to be even more certain, we should directly compare the DNA of Ann in Sweden (a direct descendant of the Swedish Carl Victor) with that of Denise (a direct descendant of the Carl Victor in Chicago).

A comparison between the DNA samples from Diane Aldrich and me. Each line represents on of the 23 chromosomes, and the dark purple parts highlight DNA that is identical between us

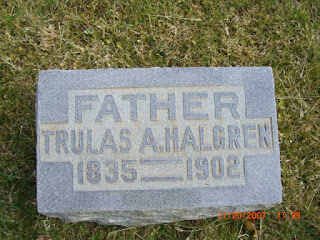

So, I conclude that the Carl Victor (Karlstad) and Carl Victor (Chicago) are one and the same person. This opened up a whole new branch of the family that I hadn't known about. It turns out that in America Carl Victor married Augusta Johnson and together they had 6 children (that I know of): Hugo Victor (1884-1939), Victoria (~1891-1936), Clara Cecilia (1892-1896), a child unnamed in the records (1894-1894), Thekla Elvira (1895-1896), and Albin August (1897-1965). The family did move from Chicago to New York City in the mid 1880s. Oscar, the grandfather of Joyce and Denise, shortened the last name to Bartel, but his siblings kept the name Barthelson. Denise has been so very generous and has shared several pictures of the people I've mentioned in this post:

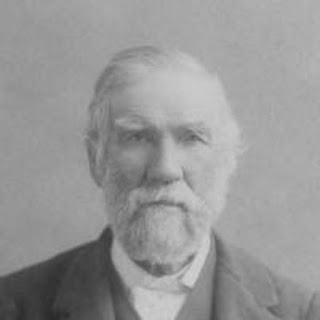

The first picture is the man himself, Carl Victor Barthelson. Actually, on the back of the photo he's identified as Gustav Victor Barthelson and cited as the father of Albin. On the whole, I'm inclined to accept that this is Carl. There is also another photo taken in Chicago in which the person is only identified as a Barthelson. Since the family left Chicago for New York in the 1880s, it's very tempting to conclude that this also has to be Carl. Do you see a resemblance with the last picture?

Finally, here's a picture dated 1926 of Carl Victor's wife Augusta together with her eldest son, Oscar James Napolien Bartel.

In closing, I want to make it clear that all of the hard work that went into digging up all these facts and putting the pieces together in a coherent story has to be credited to Joyce, Diane, Ann, Jan, and many others. I'm only the reporter. The only thing substantive that I did was to submit a couple of samples for DNA analysis.