The Search for Lottie’s Father

For several months, now, my research time has been consumed with several cases of unknown parents. I started with one case from Ireland, on my maternal grandmother’s Driscoll/Collins side of the family, and this has now grown into four intertwined cases of adoption. There’s also an interesting question for me from Sweden, and this is to try to discover the father of my great grandmother, Lottie Barthelsson. Lottie – Johanna Charlotta – was born on 27 Dec 1861 in the small town of Hallstahammar, in Västmanland. Her birth and baptism can be found in the parish book, and while the name of her mother was recorded, there was nothing identifying her father. Figuring out who he might have been, now over 160 years later, is clearly impossible to do if we have to rely only on the documentary record. With the coming of DNA testing, though, we have a whole new line of evidence of relationships available. So, with the bravado that comes with ignorance, I thought that I would see how much I could learn about the identity of this mysterious great great grandfather – let’s call him Oskar.

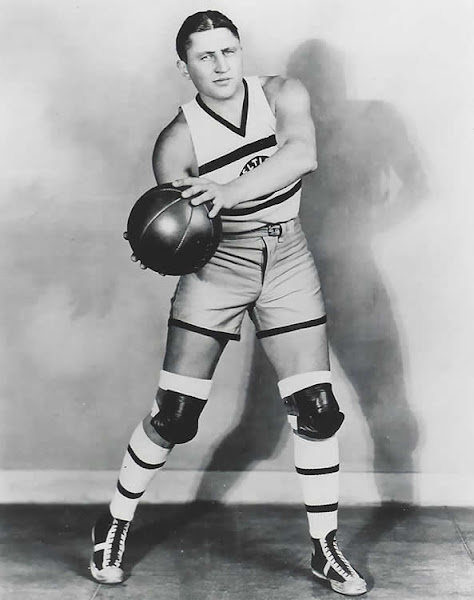

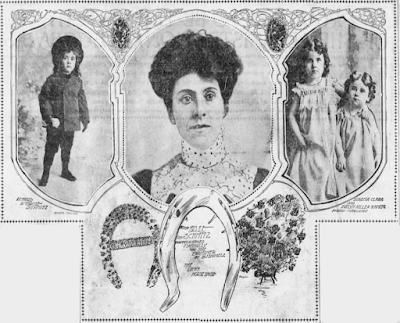

Lottie Barthelsson (right) and her daughter Wilma. Photo courtesy of Hans Malmkvist.

Lottie Barthelsson (right) and her daughter Wilma. Photo courtesy of Hans Malmkvist.

As a bit of background, each of us inherits a more-or-less random half of our DNA from each parent. Each of my grandparents contributed about one-fourth of my DNA, and each great grandparent about one-eighth. That means that the mystery man passed on to me roughly one-sixteenth of my DNA. If I could find other people who also shared pieces of that DNA, then I might be able to home in on the answer to my question.

Although this sounds reasonable in theory, let’s look at how much DNA I’m talking about. If I convert the amount of shared DNA from fractions to a measure of size called centimorgans (cM), then I should share 3485 cM with each of my parents; This quantity, approximately, drops by half with each generation. So, the amount of DNA I would expect to share with Oskar would be about 443 cM. That’s not a whole lot of DNA to work with. I could increase the amount of DNA, though, by including DNA from other descendants of Oskar.

Where could this DNA come from? Let’s review what we know about Oskar’s descendants. Lottie’s mother had only the single child. Lottie herself had only two children that survived to adulthood, and only one of them, Fred Johnson (aka Arthur Westerlund) had descendants. We “know” that Fred had five children: Alfred (born 1920), Eddie (born 1924), Joe (born 1928), Phyllis (born 1931), and my dad, Norman (born 1933). Phyllis was the last surviving child of the family, and, fortunately, she took a DNA test before she passed. Therefore, she is the closest descendant of Oskar (4 generations away) for whom we have this genetic information. We would expect that she had 887 cM that she inherited from Oskar. That’s the average amount; in the real world the known range in the amount of DNA shared with a great grandparent runs from 485–1486 cM (data from the Shared Centimorgan Tool at the DNA Painter website).

My grandmother, Nellie Shipman, surrounded by her children. Standing in the back, left to right: daughter-in-law Betty, Joe, Alfred. Middle: stepson Bruce Shipman, Nellie, Eddie. Bottom: Norman, Phyllis.

My grandmother, Nellie Shipman, surrounded by her children. Standing in the back, left to right: daughter-in-law Betty, Joe, Alfred. Middle: stepson Bruce Shipman, Nellie, Eddie. Bottom: Norman, Phyllis.

Phyllis’s brother Alfred had no children of his own, as far as I know. But Eddie, Joe, and Norman did, and those children would have inherited different pieces of DNA from Oskar. There’s almost certainly some overlap in Oskar’s DNA among the children, but likely each will have inherited some unique chunks of their own. Taken all together, then, we can increase the amount of Oskar’s DNA available, and therefore increase our chances of finding matches out there in the rest of the world that are also somehow related to him.

I’ve taken a couple of different DNA tests, and I recruited my brother and sister to do so as well. Therefore, we had DNA from the lines of two of Fred Johnson’s children, Phyllis and Norman. To get representation from his other two children, I asked my cousins RWJ (son of Eddie) and MBJ (daughter of Joe) if they would be willing to take the DNA test from Ancestry.com. I’m very grateful that they consented: thanks again for that! When the results would come in, we’d have DNA from all of Fred’s children (except Alfred, of course). The search for Lottie’s father could then continue with a better, larger sample of Oskar’s DNA.

Be Careful What You Ask For

The companies offering DNA tests for genealogical use – Ancestry, MyHeritage, 23andMe, Family Tree DNA, etc. – always caution you that the results they report may not be what you expect. Please take that into consideration before you read any further. What was my expectation? These two new tests were for first cousins, so let’s look at the overall picture of RWJ’s results. According to the Shared Centimorgan Tool, first cousins will share, on average, 866 cM of DNA, and the actual range that’s been observed goes from 396 to 1397 cM. RWJ shares 845 cM with me, 713 cM with my brother, and 1041 cM with my sister. All these values fall in the expected range. He also shares 1732 cM with his Aunt Phyllis, very nearly the average (1741 cM) for an aunt-nephew relationship (range 1201–2282 cM). No surprises there at all.

Graph showing the frequency of amounts of DNA shared between documented first cousins. The average amount that first cousins share is 866 cM; higher and lower amounts have been observed, but the greater the difference from the average, the less often that is observed. Total number of first cousins: 3,337. Chart from DNA Painter.

Graph showing the frequency of amounts of DNA shared between documented first cousins. The average amount that first cousins share is 866 cM; higher and lower amounts have been observed, but the greater the difference from the average, the less often that is observed. Total number of first cousins: 3,337. Chart from DNA Painter.

This is the point where everything went sideways. RWJ’s results came in first, and then MBJ’s came in a few weeks later. She was the one that first noticed something odd about the results: where were all the Swedish relatives? In her list of Ancestry.com matches, the first one with a possible Swedish name (Johnson) was 81st on the list (ranked by amount of shared DNA) at 43 cM. On MyHeritage, a database more widely used by Europeans, I found a Carlson match in position number 22 (54 cM). To compare with my own test, the first Swedish match was number 40 (67 cM) on Ancestry and number 13 on MyHeritage (74 cM). Further, I couldn’t find any of the Swedish matches that I know are my relatives in her list of matches.

The discrepancies in the match lists seemed unusual, and then I looked at the amounts of DNA involved. MBJ shares 313 cM of DNA with me, 402 cM with my brother, and 296 cM with my sister. Recall from above, that the minimum amount of DNA that has been recorded between first cousins in the Shared Centimorgan Tool is 396, and so the values for both my sister and me are too low. MBJ shares 723 cM with her Aunt Phyllis, 478 cM less than the empirically observed minimum! What’s going on?

With a closer look at MBJ’s shared match list, that is, people with whom she shares DNA, there were several names that I recognized. All of these are related to our grandmother, Ellen (Nellie) White, Fred Johnson’s wife. But none of them are related to both Fred and Nellie. The only possible conclusion is that while Nellie was MBJ’s grandmother, Fred was not her grandfather. In other words, Joe had a different father than his siblings Eddie, Phyllis and Norman. We can probably throw Alfred into that group as well, since there’s something of a physical resemblance between him and Fred.

From a Mystery Great Great Grandfather to a Mystery Father

If Joe’s father wasn’t Fred, then who could it have been? My research question had shifted from trying to discover who Oskar might have been to trying to suss out who this father was. The strategy for answering the questions, though, remained the same. The idea is to look at the people in the list of shared DNA matches, then look at their family trees, and find where their family trees overlap. Ideally, there would be a single lineage that all the shared matches have in common, and it’s in that lineage that I would then be looking to find one or more men who were in the right place at the right time and of the right age to have been Joe’s father. This was made a bit more difficult in practice because I haven’t worked out the family tree of MBJ’s mother, Elizabeth Smith, to any depth. Therefore, a lot of the unfamiliar name are related to this Smith line, and not to Joe’s mysterious father.

When MBJ pointed out to me the lack of Swedish names in her shared match list, there was one thing that did jump out to me: there seemed to be a surprising number of French names. In particular, these names were of French Canadian origin. In fact, number 6 of MBJ’s shared matches on MyHeritage is a young lady with French Canadian ancestry and quite a large amount of shared DNA, 118.5 cM. This match also had a fairly decent family tree worked out, with 108 people in it. This seemed like a good place to begin my research. I’m also a bit skeptical, so where shared matches had family trees available, I did my best to find the evidence myself, rather than just trust that their work was correct. I did find some significant errors in this process, and so I think my jaundiced eye was worthwhile. In many cases, though, the shared match did not have a family tree available, and so I had to work that out for myself from scratch.

To cut a long story short, I found 16 people that shared DNA with MBJ. I was able to work out their family trees and did discover a single point where all these trees tied together. This is the couple of Antoine Plante (born 1793) and Marie Marguerite Ouellet (born 1794). They were both born in Saint-Cuthbert in the province of Québec, roughly 55 miles (88 km) northeast of Montréal and 137 miles (220 km) southwest of Québec City, on the north side of the Saint Lawrence River. They had a total of 16 children! I didn’t trace the descendants of all of them, though, just those that linked up to the DNA matches.

The next problem, now that I had a “master tree” of the descendants of Antoine and Marguerite, was to figure out where MBJ best fitted into that tree. To do this I used another tool available at the DNA Painter website, one called WATO. The acronym WATO stands for What Are The Odds. We start with the question of who was MBJ’s paternal grandfather, and we have a tree built with her shared DNA matches. Importantly, we not only know that they match, but we know how much DNA each of those matches shares with her. The tool then uses information from the Shared Centimorgan Tool to calculate the probability that, say, a person that shares 244 cM of DNA is MBJ’s first cousin, first cousin once removed, second cousin, and so on through all the list of possible relationships. It does that simultaneously for all the DNA matches in the tree, and then shows where in the tree our subject – MBJ in this case – could possibly fit. The cool part is that it compares the chances of different scenarios and ranks them. Some of these hypotheses can then be eliminated with other evidence.

Results from the WATO tool. The names of living persons have been removed. The green boxes are people who lived in or near Ilion. The brown boxes are the living persons. Possible positions that MBJ could fit in this tree are labeled as Hypothesis. The value of the score for each hypothesis reflects the chance that the hypothesis could be true given the amount of shared DNA. The individual values themselves are meaningless, but the comparison between two scores is a measure of how much on hypothesis is more likely than the other. The strongest is Hypothesis 9 (score 50,918).

Results from the WATO tool. The names of living persons have been removed. The green boxes are people who lived in or near Ilion. The brown boxes are the living persons. Possible positions that MBJ could fit in this tree are labeled as Hypothesis. The value of the score for each hypothesis reflects the chance that the hypothesis could be true given the amount of shared DNA. The individual values themselves are meaningless, but the comparison between two scores is a measure of how much on hypothesis is more likely than the other. The strongest is Hypothesis 9 (score 50,918).

The most likely scenario found by the WATO tool is that MBJ is the grandchild of a man named William Peltier. This hypothesis is about twice as likely as the next set of four hypotheses, all of which are that she is the grandchild of one of Peltier’s siblings. Two of those we can eliminate, since they were William’s sisters, and we know that the missing grandparent was a man. That leaves us with three possibilities for Joe’s father: William, Daniel, and Fred Peltier. Actually, there is another brother, Joseph (for some reason called Tim!), but we have DNA for two of his great grandchildren and one great great grandchild, and the amount is too small for this to be as likely a scenario.

So, who might have been in the right place at the right time and of the right age? William was born in 1899, Daniel in 1898, and Fred in 1903, and so they would have been from 25–30 years old when Joe was born in Ilion, New York. Therefore, they were all of the “right age”: Nellie was 28 when Joe was born. Daniel Agustus Peltier was a transfer baggage man at the Richland, New York station of the New York Central Railroad. He died in 1932 in Richland and had never married or had any known children. He was born in Little Falls (11 miles east of Ilion), but had been living in Richland (72 miles northwest from Ilion) for 15 years.

Frederick Philip Peltier (1903–1957) was born in West Albany, New York. Early in life his parents moved west to Frankfort, the village abutting Ilion on the west. We find records of him there in the 1905, 1910, and 1915 censuses. He was a “chef;” I use the term with some caution, since the establishments he worked in would seem to call more for a short-order cook than a chef of haute cuisine. For a while in and around 1932 he was the manager of Central Square Lunch in Ilion. He married Mary Whalen in 1924, and together they had a son also named Frederick who was born in 1925. The couple must have divorced fairly shortly afterward, because Mary married Frank DeMola in 1935. (To make the story more complicated – and who doesn’t love a good complication – Frank was the widower of Fred’s sister Delia.) Fred served time in Sing Sing Prison for grand larceny. He was convicted of stealing a car valued at $200 in a parking lot at night in Ilion while intoxicated. Interestingly, his accomplice was a Jerry Whalen. I hadn’t noticed that Jerry had the same surname as Fred’s wife. Interesting. To wrap this up, Fred died in Miami in 1957, and he was unmarried at the time. Conclusion: the evidence is all consistent with the possibility of Fred being the unknown father.

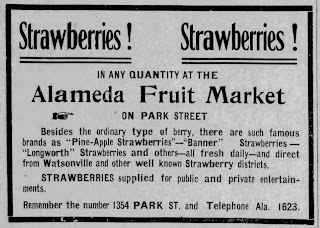

Advertisement for Central Square Lunch during the period in which it was managed by Fred Peltier. Published in the Utica Daily Press, 14 May 1932.

Advertisement for Central Square Lunch during the period in which it was managed by Fred Peltier. Published in the Utica Daily Press, 14 May 1932.

Finally, we turn to William Joseph Peltier (1898–1967). Remember, he is the most likely parent of Joe according to the WATO tool. William was born in Colonie, near Albany, but then lived from at least 1905 to 1915 in Frankfort. In 1919 he married Blanche Irene Cavanaugh, who was from Pulaski in Oswego County. They had three children, Ethel May (born 1924), Alice Louise (born 1929), and William John (born 1931). In 1930 the family is recorded in the census from Lyons, New York in Wayne County, 118 miles west of Ilion. He was a machinist at the Rome Manufacturing Company and the General Cable Corporation. He died in 1967 in Rome, New York.

I’ve left out one important detail. In the 1925 Census for the state of New York, William, Blanche, and their first child Ethel were living in Ilion. Helpfully, the census also gives their street address: 131 West Clark Street. I didn’t notice this at first, but once I did the alarm bells started going off in my head. Recall that we’re searching for the father of the child born to Nellie (White) Johnson. In 1925, Nellie was living with her father (Luke White), mother (Elizabeth White née Farnham), husband (Fred Johnson) and two boys (Alfred and Edward) directly across the street from William at 132 West Clark!

The house at 132 West Clark Street, Ilion. In 1925 it was occupied by Luke and Elizabeth White, Fred and Nellie Johnson, and their sons Alfred and Edward. William Peltier lived in the house on the opposite side of the street. Image taken in 2021 by Google.

The house at 132 West Clark Street, Ilion. In 1925 it was occupied by Luke and Elizabeth White, Fred and Nellie Johnson, and their sons Alfred and Edward. William Peltier lived in the house on the opposite side of the street. Image taken in 2021 by Google.

Unfortunately, there’s a gap of two full years between the official date of the census (01 June 1925) and conception of Joe, sometime around June of 1927. William’s obituary, published on 26 December 1967 in The Palladium-Times in Oswego states that he had arrived “here” 28 years earlier, so roughly in 1939. The 1940 Federal census records that William was living in Ilion on 01 April 1935. I’ve not been able to find any city directories for the critical period of 1925–1927 to establish where William might have been living at the time. Conclusion: as with Fred, the evidence is consistent with the hypothesis that William was Joe’s father, and there is the additional factor of physical proximity with Nellie.

I will admit that it is very, very tempting to decisively conclude that William was the father of my Uncle Joe. That is my tentative conclusion, but I would urge a bit of caution. William did live right across the street at about the right time. But he had another brother, Fred, also living in Ilion at the time, and it’s reasonable to suspect that Fred might have been at the home on West Clark Street on occasion. William’s middle name was Joseph. However, Nellie’s mother had a brother also named Joseph, who had died as a young child. One way to possibly resolve the question is to see how much DNA the living descendants of Fred share with MBJ. I’ve tried to initiate contact with them, but so far I’ve not gotten any response. Of course, there’s the other brother, Daniel, but since he has no known descendants, we’ll probably never be able to eliminate him as a possibility.

It’s a Small, Small World

As a young boy my dad lived with Joe and Betty in town to go to school while his mother and stepfather lived on a farm in the country. My Uncle Joe was a prominent figure in my life after my family moved back to Ilion in 1967. We went fishing (I was no end of frustration for tangling the fishing line on the reel); he gave me a couple of pairs of work gloves and a polka-dot hat when I worked summers at the Cranberry Lake Biological Station in the Adirondacks; and when I left to go to college in Syracuse he put a Syracuse University sticker on his backhoe. He died in 2008 and Aunt Betty passed in 2011. There was a ceremony in Union Cemetery when the urns containing their ashes were placed there, and afterwards everyone went to Donna’s Diner on Route 5 in East Herkimer to eat, talk, share…. The Donna of Donna’s Diner was Donna Marie Krouse (1946–2016), wife of Thomas James Graham (1942–2021). Joe and Tom were good friends. Tom had lost an arm in a hunting accident, and the story my mother told me is that Joe would help out at the restaurant, for example, in unloading deliveries. The funny thing I stumbled across is that, if we assume that Joe was the son of William Peltier, then Tom was his first cousin once removed. Was this coincidental, a case of similar personalities gravitating to one another? Or did they know something that none of us were in on. I wonder.

Notes

- Those of us of a certain age will recall the rest of that chorus: You can’t always get what you want, but if you try sometime, you just might find you get what you need.

- I used the name Oskar to refer to the unknown father of Lottie because that was the name she gave for her marriage certificate in 1886.

- I did consult with Joe's daughters to be sure that they had no objections to sharing the story with you. I have not used my cousins' names here, but I doubt that is fooling many readers!

- The picture of Joe Johnson comes from the wedding photo of my parents.