We’ve all done it: you shake a can of your favorite carbonated beverage, pop the top, and… well, you know what happens next. This happened to me a few months ago when I tried to explore some of my DNA matches.

The number of DNA matches that you’ll get is overwhelming, literally thousands. Most of these, as you’d expect, are pretty remote. One of the rules of thumb is that any match of less than 7 cM has a pretty high chance of being just a random match. That’s 7 cM out of a total of something near 7,000, or 0.1%. Most of the names of my DNA matches are entirely meaningless, and I have to try to dig in deeper to discover how they’re related. My usual strategy is to start with matches that are associated with their own family trees, the bigger the tree, the better. The next criterion is to research matches that have “unusual” names. If all you have to work with is the name, and the name is something super common like, say, Mary Jones, you’re going to run into a lot of false leads.

All this is to explain how I popped the top on my can of soda. It was a match on 23andMe; I’m going to purposely be vague on identification of these users because, you know, this can be a touchy issue. My other little dirty secret is that, for living people, Facebook is simultaneously a blessing and a curse. Some folks are extremely reticent to post anything of a personal nature on Facebook, but others spill their guts! For this DNA match that I began to explore I was able to find his/her site on Facebook. Unfortunately, that didn’t really help me out very much, that is, until I started exploring one of their friends, a sibling. Pop!

It took about two weeks worth of work, but I was able to follow this lead back five generations before it ran dry. At the end of the line was a couple by the name of Daniel O’Brien and Mary Driscoll. Of course, the wife's surname caught my attention since that was the maiden name of my great grandmother.

View of the townland of Bawngare, home of Daniel O'Brien and Mary Driscoll.

View of the townland of Bawngare, home of Daniel O'Brien and Mary Driscoll.

Mary Driscoll married Daniel O’Brien on 24 Feb 1846 in the parish of Skibbereen and Rath in West Cork. They lived in Bawngare in the parish of Aughadown. In the 21 years between 1847 and 1868, Mary gave birth to eleven children. I’ve been able to trace 16 DNA matches to the descendants of the children of Mary and Daniel O’Brien so far: four to their son Daniel, six to their daughter Katherine, one to daughter Margaret, two to daughter Hannah, and two to daugher Mary. It was pretty clear to me that we’re related to Mary Driscoll, but the question is: how?

Husband Daniel O’Brien died in 1874 at the age of 57. Mary, however, lived until 06 Jan 1914, and at that time the civil registration of her death claimed that she was 88 years old (so, roughly, born in 1826). The description of her funeral that was published in the Skibbereen Eagle turned out to be the key to the job of piecing together her family. Here’s the beginning of the obituary:

Mrs. Mary O’Brien, Bawngare, Aughadown.

It is with feelings of deep regret we have to chronicle the death of this respectable inhabitant, which took place at her residence on Tuesday morning. She was greatly respected by all who knew her for her high person, worth, and character. Belonging to one of the oldest and most respected families in the neighbourhood, where her ancestors have settled for many generations past in the district. Her death is sincerely mourned by a wide circle of relations and friends. The funeral, which took place for the Abbey, was, notwithstanding the inclemency of the weather was one of the largest seen in the district for some time.

The officiating clergymen were Rev J O’Sullivan, P P, Aughadown; Rec T Hil, C.C., do.

Then, the important part:

The chief mourners were – Daniel O’Brien, R.D.C. (son) [RDC = Rural District Council], Mrs O’Brien (daughter-in-law), Mary, Kate, John, William, Ellie, Dan, Stephen, Denis, Bridie, Kathleen, Michael, (grand-children), Mrs. Collins (sister), Timothy Driscoll (nephew), Mrs. McCarthy, Mrs Holland, Margaret M Collins (nieces) ....

Aughadown Cemetery, from the Skibbereen Heritage Centre. While Mary O'Brien lived in Aughadown Parish, I don't know in which graveyard she was buried.

Aughadown Cemetery, from the Skibbereen Heritage Centre. While Mary O'Brien lived in Aughadown Parish, I don't know in which graveyard she was buried.

Mrs. O’Brien, Daniel’s wife, was named Mary Anne Dwyer (1866 – 1952). The grandchildren listed were all the children of Daniel and Mary Anne. I still have not identified exactly who the nephew Timothy Driscoll was. After some digging, I was able to uncover that the sister, Mrs. Collins, was named Hanora. Margaret Mary Collins, as I expected, was her daughter. The other two nieces were more difficult to identify. I finally discovered that Mrs. McCarthy was another of Hanora’s daughters, Rebecca. The mysterious Mrs. Holland was more of a struggle. I will return to her shortly.

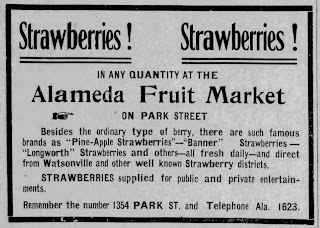

Five of the daughters of Daniel and Mary O’Brien – Mary, Margaret, Annie, Hannah, and Ellen – emigrated to the United States and settled in California, living in San Francisco and Alameda Counties or a bit farther south in the coastal farmlands of Monterey and Santa Cruz Counties. Knowing that, my interest was piqued when I started pursuing a new and different set of DNA matches, matches who lived in exactly the same area of California.

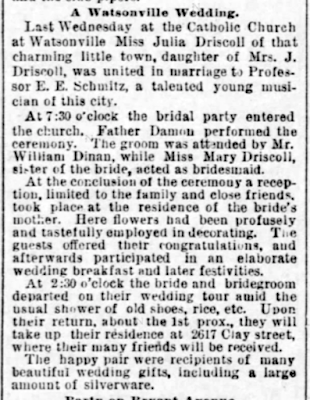

These new matches, as far as the records would take me, traced back to a couple named Jeremiah Driscoll and Johanna Hickey. The American records say that Jeremiah was born around 1830 and died in 1884. He originally went to northern California to work in the mines, and then moved south to settle in the Pajaro Valley of Santa Cruz County, near the modern town of Watsonville. He and Johanna had nine children together. I’ll have more to say about Jeremiah’s family in a subsequent post. I have three DNA links with Jeremiah’s descendants, both through his son Richard.

In the 1860 Federal Census Jeremiah, age 27, is recorded living with his wife Hannah and their newborn, first-born daughter, Mary. Also listed is a man named Daniel Driscoll, age 29, a farm laborer born in Ireland. On the basis of this record, I have seen some speculation that this Daniel was Jeremiah’s brother.

To briefly review, my 2nd great grandfather, Timothy Driscoll, was born sometime around 1836. Mary Driscoll, a relative of some sort, was born around 1826. She had a sister Hanora (Mrs. Collins). Jeremiah Driscoll was supposedly born in 1830. And, finally, Jeremiah may have had an older brother Daniel. How to reconcile all these facts? I suspected that all of these people – Timothy, Mary, Hanora, Jeremiah, and Daniel – might be brothers and sisters. But that guess was based only on the DNA matches and the rough similarity of their ages (born about 1826 to 1836).

The Mysterious Mrs. Holland

There was one more loose thread: the mysterious niece, Mrs. Holland, mentioned in Mary O’Brien’s obituary. Who was she? To resolve this I used the church and civil registrations of births and marriages in Ireland. The civil registrations began in 1864, and I presumed and hoped that a niece of Mary would likely have been married after that date. This was important because the church records usually would only show the names of the bride and groom and the names of the witnesses. They might also include the name of the officiant, and even less commonly where the couple came from. The civil records, in contrast, give all of that information, always with the homes of both bride and groom, and the names of the couple’s fathers as well. So there’s a lot more information to work with there.

Home page of IrishGenealogy.ie, a source for transcriptions and images of church and civil records in Ireland.

Home page of IrishGenealogy.ie, a source for transcriptions and images of church and civil records in Ireland. In the civil records (accessed through irishgenealogy.ie) I found that between 1890 and 1914 there were eight marriages recorded in the D.E.D. (District Electoral Division) of Skibbereen records and two in the D.E.D. of Schull in which the groom was named Holland. (Thank goodness for uncommon names!) I also assumed that when the newspaper reported that Mrs. Holland was a niece of the deceased Mary O’Brien they were being literal. That is, that Mrs. Holland was either the daughter of one of Mary’s siblings, or she was the daughter of one of Daniel O’Brien’s siblings. Therefore, if Mrs. Holland was the daughter of a brother or sister of Mary, then her maiden name would either have been Driscoll (if she were the daughter of a brother) or her mother’s maiden name would have been Driscoll. I could get this information from Mrs. Holland’s marriage record or from the marriage record of her mother. Similarly, if Mrs. Holland were the daughter of one of Daniel O’Brien’s siblings, then either her maiden name was a variant of O’Brien or her mother’s maiden name was. Finally, the civil registration of the marriage of Mrs. Holland would tell me the name and residence of her father.

Civil registration of the marriage of Patrick Holland and Annie Driscoll.

Civil registration of the marriage of Patrick Holland and Annie Driscoll.The only marriage that fit these criteria occurred on 19 Feb 1903 in Rath Church in which Patrick Holland and Annie Driscoll were wedded. Annie was recorded to be living in Ardagh at the time of her marriage, and her father’s name was Patrick Driscoll. I then checked the civil birth records for an Annie born to father Patrick Driscoll in the years 1864 – 1883 (so that Annie would have been at least 18 when she married). There were three such cases, but all born in Cork City. I then expanded my search into the church records, and found a baptism for a Nancy Driscoll, 15 Jun 1865, in the parish of Rath and The Islands. The parents of this child were Patrick Driscoll and Margaret Driscoll. Now while there is a townland called Ardagh a good distance east of the area of my focus, there were also two others in the immediate area: Ardagh North and Ardagh South. If you enlarge the image of the registration of their marriage, you'll see that one of the witnesses has a familiar name: Margaret Mary Collins. Therefore, this lead seemed very promising, and so this is where I concentrated my attention.

In the 1901 Census of Ireland for the D.E.D. of Tullagh there is a record for an Annie Driscoll (age 28) living in the home of her brother Michael (age 36) and his wife Mary in the townland of Ardagh South. I could not confidently recognize either of Annie’s parents, Patrick or Margaret, anywhere in this census. In a search of the civil death records I found one Patrick Driscoll of about the right age in the period from 1865 – 1901. This man died in 1877 at the age of 62 (therefore, born around 1815). I failed to find a Margaret, at least one that I could confidently identify as the mother of Annie. There were several possibilities, but with little information to distinguish them.

I went back and searched the birth records for children born of parents Patrick and Margaret Driscoll. I found seven, Annie being the youngest. Five of these children emigrated from Ireland and lived in either Santa Cruz or Monterey Counties in California. Coincidence? I think not! I have one DNA match with a descendant of Patrick and Margaret (and six additional matches with the descendants of that match). This reassured me that I’d been lucky enough to find the right Mrs. Holland!

Now I have another potential sibling of my 2nd great grandfather, but was it Patrick or Margaret? Both had the surname Driscoll. All told, I had six potential brothers and sisters. The next step was to try to pull all these threads together, and if they were siblings, who were their parents?

Pulling the Threads Together

For years I had despaired of learning more about the ancestry of my great-great-grandfather Tim Driscoll. Both his given name and his surname are very common in the area of West Cork. I could find lots of Tim Driscolls in the records, but I had no way of knowing which one was the right one. The same is true for all of the rest of the names I’d uncovered: Patrick, Daniel, Jeremiah, Mary, Hanora, Margaret, and Johanna. Then the thought occurred to me that even if I couldn’t confidently associate an individual with a specific record, perhaps I could make some progress if I looked at this as a family. My question, therefore, became: how many families in West Cork had children with all of the names Mary, Jeremiah, Timothy, and Hanora? I didn’t include Daniel in this list because the evidence was pretty slim that he was actually Jeremiah’s brother. Also, I didn’t know if it was Patrick or Margaret who was a member of this group.

I have a long list of reasons why this search strategy could fail. But basically, here’s what I did. I tabulated the parents and the baptismal date for all the Driscoll children with these names who were born between 1820 and 1840 in the parishes of Aughadown, Caharagh, Muintervara, Rath and The Islands, Schull East, Schull West, and Skibbereen. A total of 479 families in these West Cork parishes had at least one child with the name Mary, Jeremiah, Hanora, or Timothy. But I was pleasantly surprised – no, ecstatic – to find that only one family had kids with all four of these names.

The parents in this family were named John Driscoll and Mary Hourihane. The baptismal dates for the four children where Mary, 15 Apr 1825; Jeremiah, 08 Feb 1829; Honora, 09 Jun 1833; and Timothy, 18 May 1835. This is exactly the same birth order that I’d gleaned from other records, and the dates are close. Remember, that in those days people were a lot more free and easy with this information than we are today. For two of the baptisms the townland is recorded: Ballymacrown. This is the same place that my 2nd great grandparents Tim Driscoll and Ellen Collins had lived. I then searched the baptismal records of Skibbereen to find any other children of that couple, and I came up with four more names: Daniel, baptized 04 Feb 1827 from Ballymacrown; John, 23 Jan 1831 also from Ballymacrown; Michael, 08 Apr 1837; and Johanna, 15 Jun 1840.

Registration of the baptism of Deniel Driscoll in the register of Skibbereen (Creagh and Sullon) parish.

Registration of the baptism of Deniel Driscoll in the register of Skibbereen (Creagh and Sullon) parish.

The baptismal record for Daniel corroborates the interpretation of the 1860 U.S. census that Jeremiah had a brother by that name who was two years older. But there’s also something else interesting in that record: Daniel’s father’s name was recorded as John Bawn Driscoll. (Actually, the irishgenealogy.ie transcription was John Bacon Driscoll, but a look at the image of the original register entry led me to a different interpretation.) Now, it’s not unusual that when surnames are so common that they don’t adequately serve to distinguish people, then new names can be adopted. Such a name is referred to as an agnomen. Bawn or Bane is a fairly common agnomen in Ireland. The name is derived from the Irish word bán, which means white, and it commonly refers to a person or an ancestor who was blonde or fair-haired. I went back and searched for children of a couple named John Bawn and Mary Hourihane, and found yet another child, Cornelius, boaptized 24 Oct 1823 from Ballymacrown.

There’s one piece missing though: have you spotted it yet? Answer: there is neither a Patrick nor a Margaret in the list of children. (Remember, these were the parents of the mysterious Mrs. Holland.) However, I redid part of the search on another website, FindMyFamily, and there I found a Margaret. She, too, was born in Ballymacrown and baptized on 31 Jul 1821. Apparently, the transcribers for irishgenealogy.ie had missed this entry in the baptismal registers because instead of the record starting with the child’s name, it began with the name of the priest doing the baptism.

We may not be done yet: I searched the baptismal records for children of John Bawn from Ballymacrown and came up with yet another child: Catherine, baptized 19 Aug 1821. In this case, though, the mother is recorded as Catharine Sheehane. It’s difficult to be certain, but it’s at least plausible that Mary Hourihane was John (Bawn) Driscoll’s second wife.

To summarize, in the table below I’ve compared the potential brothers and sisters of Timothy Driscoll that I’ve found using DNA and later records, with the baptismal records of the children of John Driscoll and Mary Hourihane.

There were lots of assumptions that I had to make at each step in this research, but even so, I find the results to be compelling. The best test of these ideas will be to trace any descendants of these new members of the family – new to me at any rate – and see if we share any DNA. Much of this post has focused on the research process, but in the course of it I came across several interesting stories. My plan is to share those in the next few posts.